It’s quite difficult writing Mediaeval novels when you can’t mention clocks, minutes and seconds.

Moments…yes…but of course time wasn’t measured in the same way as we measure it today. Before clocks (and they, as we know them, came about in around the middle of the 14th century,) it was impossible to measure time with any accuracy. Water clocks were known from early times. These, known as clepsydra measured time by the regulated flow of liquid into (inflow type) or out from (outflow type) a vessel, and where the amount is then measured. These were notoriously unreliable and required human intervention in large measure.

Once the escapement movement was invented we were well on the way to being able to measure time accurately and easily, though one could never have had a portable version, these clocks were so huge. A clepsydra from the third century B.C.

A clepsydra from the third century B.C.

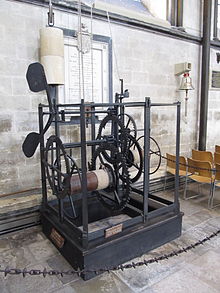

The clock in Salisbury Cathedral thought to date from 1386.

The clock in Salisbury Cathedral thought to date from 1386.

So how did our ancestors know what time of day it was?

Mass Dial at St. John’s Devizes Wiltshire.

Mass Dial at St. John’s Devizes Wiltshire.

In order to make sure that mass was said at the correct time, little sun dials were scratched into the wall and a gnomen or prong fixed to the church wall. Known as mass dials, they would throw a shadow onto a base plate to indicate when mass should be said. You’ll find one of these playing a big part in my first Romance novel, Forceleap Farm.

Personally people, I’m sure, had a better idea of the passage of time, in the Middle Ages much as dogs do today. They always seem to know when it’s dinner time or time for a walk.

Personally people, I’m sure, had a better idea of the passage of time, in the Middle Ages much as dogs do today. They always seem to know when it’s dinner time or time for a walk.

But how would you, let’s say arrange to meet someone at a certain time?

Well, you could organise to meet them when the Angelus bell rang, or just before Vespers or at Matins, for example. Bells were rung in both parish church and abbeys, priories and cathedrals to show the times when folk might come to church.

If you wanted to know how much time something took you, you might recite a prayer or several prayers, like a Paternoster (Our Father) or an Ave Maria. You might like to measure the time by how long it took you to put your clothes on, or your boots. Or maybe walk a distance. This one was quite popular. Everyone knew how long things took because they all did these things and it was easy to compare.

If you could afford it, you might have a graduated candle which would give you the hours depending upon how it burned. No one was finicky about the minutes. No one had to make sure they were somewhere dead on time. Except mass. It wasn’t the religious groups who needed to know what the time was. It was astronomers who needed to understand the passage of time and clocks really came out of their needs. Most showed the phases of the moon etc. and you’ll meet that type of machine when I publish my second romance novel, Hunting the Wren.

Candle clock – the precursor to the alarm clock. The wax would melt and the nail would fall with a clatter, waking you up…you hoped.

Candle clock – the precursor to the alarm clock. The wax would melt and the nail would fall with a clatter, waking you up…you hoped.

Who made these clever clocks? Well it was blacksmiths and coppersmiths but again they weren’t widespread. At the time I write about there were none documented. So you just had to make an educated guess at time. Most people got up with the dawn which naturally varied with the time of year and retired (if they could not afford to light the darkness) when the sun was well and truly down.

Prime, as you might guess, was the first hour. The third hour, terce, was about halfway between daybreak and noon. Sext, or noon, was the sixth hour. The ninth hour, nones, was about halfway between noon and sunset. Vespers was the twelfth hour, or sunset. All these times would be marked by the ringing of church bells and, because no one lived too far away from bells ( except perhaps anchorites and outlaws,) they’d know what time it was.

No escape then… (pun intended.)